Study finds that space matters for student learning in fraternity houses

It’s hard to study on a dance floor – even if it’s empty.

That’s what members of one William & Mary fraternity told Jim Barber in 2012 when the chapter was housed in what was then called “the units.” Those facilities included a common entry area, which students would use for both for social gatherings and studying.

“There really isn’t a learning space, and that’s a big issue,” one student told Barber. “This is a space here – ‘the dance floor,’ as we call it. People sort of come down here late at night [to study], sometimes the basement, but even then it’s really hard for me to focus.”

When Barber, an assistant professor of education, heard that some of William & Mary’s fraternities would be moving into new housing in 2013, he saw an opportunity for research on student learning. Nationally, Barber is regarded as an expert in the areas of college student learning and development, and has conducted research in this arena for over a decade.

“I saw a once-in-a-generation opportunity to look at this transition, and I really wanted to study how that change of environment was perceived by the students,” he said.

And so, he developed a longitudinal study to see how students viewed the two different sets of fraternity houses as learning environments – if, indeed, they did at all. Barber detailed his findings in a research paper presented to the American Educational Research Association (AERA), the premier national research society on education. His work could help college administrators beyond W&M shape fraternity housing – and other campus places – as learning environments.

With the founding of Phi Beta Kappa in 1776, William & Mary became the birthplace of the American college fraternity. For over 235 years, the campus has been home to a fraternity and sorority community. Nationwide, fraternal organizations own and manage $3 billion in student housing, which accommodates 250,000 students a year in 8,000 facilities, said Barber.

“Fraternity and sorority housing is not going away on college campuses,” he said. “So how can we help to shape those into environments that are more conducive to student learning and less conducive to some of the negative behaviors that we see going on?”

Two interviews, two years

Before becoming a professor, Barber worked for nearly 10 years in student affairs administration, with some of that time devoted to advising fraternities and sororities. Now on the faculty of the School of Education, Barber continues to work with fraternities and serves as the faculty fellow for the Sigma Phi Epsilon chapter at William & Mary.

When Barber heard about the housing project in 2012 and identified the research opportunity, he reached out to Vice President for Student Affairs Ginger Ambler and other members of the Division of Student Affairs. With their support, he contacted the fraternities – excluding the one he advises – and found three that were willing to participate in his study.

Within those groups, he sought out sophomores and juniors who were living in the old fraternity houses (the units) and were also planning to live in the new houses so that he could attempt to talk to the same people over the course of two years.

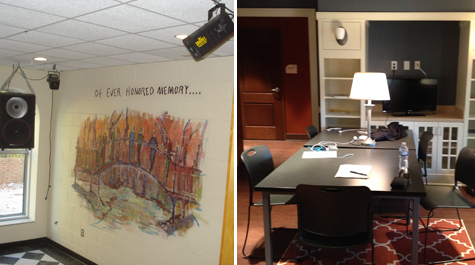

Barber first interviewed the students in the fall of 2012, conducting the queries not in a lab or office, but the fraternity houses (the units) themselves.

“I was intentional about how I did this in that I wanted to hear how students described their learning environment, but I also wanted to see if for myself,” Barber said.

Barber met the students at the houses and asked them to choose a place to sit down for the interview, so it was different every time.

“I had about a 60-minute interview with each person, asking them about the environment, about how they perceived it in connection with learning, asked about some of their study habits, work habits, where they got work done – those types of topics – and then finished each interview by asking the students to take me on a guided tour to show me the places they had talked about,” Barber said, adding that he also took photos on the tour.

The fraternities moved into the new housing in the fall of 2013, and Barber followed up with the second round of interviews in the spring of 2014.

Spaces, places and moveable furniture

Barber framed his study in terms of “spaces” and “places,” with places being the physical environments and spaces being the way students used them.

Looking at the information he collected over two years, Barber found that, often, the way that students used a place really set the tone for whether they saw it as a learning environment or not.

Take the “dance floor,” for example.

“If the way you’re thinking of a space is that this is our social space and what we use as a dance floor, it’s hard to then also think of that as a space where you’re doing academic work related to learning,” Barber said.

But in the new houses, certain rooms were designated as study spaces, and the distinction between those areas and social areas was clearer.

But in the new houses, certain rooms were designated as study spaces, and the distinction between those areas and social areas was clearer.

“It was no surprise that students tended to really gravitate toward those [study] spaces in terms of being able to do some academic work there,” he said.

Furniture, too, seemed to make a big difference.

“Students loved the moveable furniture in the new houses,” Barber said. “That was a part of each new house, several big tables they could move around to different configurations in the common space and make their own work area. Those details that seem like they wouldn’t be a big deal to students, they raved about it.”

One piece of furniture that Barber was surprised to see not often being used for learning – in either the old or new houses – was each student’s personal desk. Many of students reported trying to minimize the space that the desks took up, and so they were stacked on each other, pushed under beds or used for other purposes – such as entertainment centers.

“One of the things that surprised me was how students did or did not use their personal space in their room for studying,” he said. “I think we make assumptions that we provide every student with a desk and a chair and that it would be set up like this, where they have their computer and their lamp and they’re ready to do work, when it’s used much differently.”

Instead, many students preferred the community areas where they could configure furniture to work individually or collaboratively.

Space matters

Barber identified two main takeaways from his study: space really matters, and the way students perceive that space is important to how they use it.

In his paper, Barber suggests several implications and applications for college administrators, including the creation of curricula for fraternity learning spaces, encouragement of students’ ownership of housing and determination of the use of furniture.

Sometimes, it just takes small adjustments to make a big difference, Barber said, pointing to the easily moveable furniture in the new houses.

“In the overall budget of this project, tables and chairs were probably a small part but made a huge difference in how the students used the space,” Barber said. “Thinking about the bigger picture beyond sorority/fraternity housing and William & Mary, if investing in some really good, comfortable tables and chairs and lighting can help students re-conceptualize a space from a dance floor or a social space to one that’s more conducive to learning and academic work, that’s a great investment.”

Survey data collected by the William & Mary Department of Residence Life showed substantial increases in both overall satisfaction and the overall learning experience ratings among fraternity residents following the transition to the new houses.

Barber is currently working on revising his paper for publication in a scholarly journal, and he is thinking about a possible third phase of the study, in which he’d interview students who are currently in the fraternity houses. Barber is also interested in seeing how the units – now renovated and called Green & Gold Village – are currently being used by students for learning.

Barber sees student learning in a very integrated way, he said, and hopes studies like his will help colleges do the same, recognizing residential environments as places where learning happens while also inviting students to discuss what’s happening in their living spaces in the classroom environment.

“It’s always surprising to me how eager students are to talk about their college experience, and what they’re learning and what the learning experience is for them,” he said. “That’s always refreshing because you can see the true excitement that students have about learning.”