Where faith and school meet: W&M researcher exploring the intersection of youth spirituality, religiosity and mental health

"I am really passionate about conducting research that explores the role school mental health providers have in addressing, acknowledging, and responding to culturally diverse students and in particular students who are spiritually and religiously diverse," she said. Parker became aware of this concern when she was providing counseling support to middle and high students in public school settings. "Youth would bring up different aspects of their faith, whether questioning or referring to religious texts to keep them motivated. I found myself wondering, 'what am I supposed to do here? What do I say?'"

Parker was sensitive to the constraints created by working with minors in public school settings, but she also knew that many students wanted to talk about their faith and spirituality. She began to realize that while training programs for school mental health professionals acknowledge the diversity of faiths, they may not adequately address what that aspect of diversity means for school mental health practices.

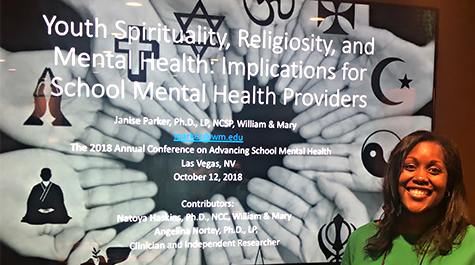

Parker began to hear similar questions about how to discuss spirituality, religion, and faith from colleagues, so she partnered with Natoya Haskins, associate professor of counselor education at W&M and Angelina Nortey, an independent researcher and clinician, to begin a deep dive into the literature that ultimately led to the development of a presentation for the conference.

"In the school psychology literature, we acknowledge faith in different ways. For example, in crisis response texts, faith is identified as a resiliency factor. Some of the common themes that I noticed was that there is a clear acknowledgment that youth mental health is influenced by students' religiosity and spirituality."

Research has shown that students who report having a high sense of religiosity/spirituality are more likely to report experiencing positive indicators of mental health (i.e., overall subjective wellbeing) and they are less likely to report experiencing more pathological indicators of mental health, for instance anxiety, depression, and engaging in risky behaviors.

"Some students even report it helps them academically," said Parker, adding that research also suggests that in some instances, a student’s experience with their religion may cause distress, which should be attended to as well. The research fueled her curiosity about interventions that effectively incorporate faith.

"Consistently, scholars emphasize that the practitioner should be mindful of the setting in which they work, with special consideration for mental health services provided in school settings," she said. "We have an ethical obligation to provide culturally sensitive and responsive services, but we are also bounded by the institution we work in, especially as it relates to the separation of church and state."

Parker is leading initial research to understand how school psychologists and school counselors incorporate professional competencies around working with students' faiths, including atheism and agnosticism, into their services. "Too often, we practitioners don’t say anything about students' religious or spiritual belief systems; we pretend it’s not there, or if we do say something about it, we hesitate to have those conversations or we may make insensitive remarks," she said.

Armed with more questions than answers, Parker gave a presentation and led a discussion with 25 attendees at the conference.

"Throughout the presentation, they were highly engaged and we all identified a need for continued research in this area," she said. Participants raised some of the challenges they are currently facing, such as how to work with the faith of students who are refugees coping with the trauma of war.

"Other conversations included the participants sharing difficult cases they have encountered and the challenges they experience when advocating for religious/spiritual youth in public school settings. As an example, one participant shared that her administrator did not want to provide a space for religious students to pray to support their social-emotional wellbeing."

In contrast, Parker recalled that mental health professionals working in faith-based private schools felt they had significant administrative support for initiating conversations around students’ religious or spiritual beliefs in relation to students’ social, emotional and behavioral functioning.

"Finally, rich and somewhat emotional dialogue occurred when we discussed the difficulties school mental health providers may experience with 'suppressing' their own beliefs when providing counseling support in school settings. Other attendees passionately shared that some students and families may not embrace the common school practice of mindfulness due to their own spiritual or religious practices or beliefs," she said.

All in all, Parker felt the conversations that emerged highlighted the need for continued scholarship in this area in the school mental health literature.

"Several participants encouraged me to keep this line of inquiry going and they thanked me for giving them a 'safe space' to have what they perceived as much needed dialogue," she said.