South Africa trip teaches W&M grad students about higher ed issues abroad

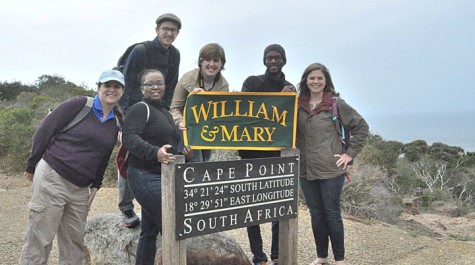

A group of graduate students with the William & Mary School of Education recently traveled to South Africa to learn about higher education and counseling in the country as it continues to evolve 21 years following the end of apartheid.

Eddie R. Cole, assistant professor of education, taught the global studies course, leading the five students over the course of two weeks from the townships of Cape Town to the halls of four universities.

“I think the trip helped provide some perspective for me and helped me realize that many of the issues we are having in the U.S. are not unique to our country,” said Katie Winstead Reichner, a doctoral student in W&M’s higher education program. “Alternately, we're doing some great things that I think other countries could learn from. Overall, it was an incredible opportunity to learn.”

This is the fourth year that the William & Mary School of Education has offered a global studies trip to graduate students, with previous trips going to Ireland, China and Italy. The goal of this year’s trip, May 20-June 3, was to continue the ongoing conversation in the School of Education about what it means, in a global context, to be a leader in higher education, said Cole.

“William & Mary has really grown into this fabric of being an international university and giving students an international experience, even on the graduate level, and I’m glad to be a part of that,” he said.

One city, two worlds

Cole, who joined the W&M faculty three years ago, had previously led a research project about faculty teaching practices in Canada, the U.S. and South Africa. So, when he was approached about leading one of the global studies trips, he chose South Africa to continue the work that he had begun. He began planning last year with help from the Reves Center of International Studies and Will Taylor, a May graduate of the higher education master’s program who blogged throughout the experience.

“South Africa is really interesting, especially if you think of America in the context of a lot of the racial discussions that are happening here right now,” said Cole. “As soon as we got there and the driver picked us up, he started describing Cape Town as one city, two worlds. There are these huge disparities in wealth and poverty and racial differences, and that really set the tone for our entire time there.”

The group began by visiting the Cape Town township of Langa, one of the areas in which black Africans were forced to live during apartheid. Non-white people, including black Africans, Indian South Africans and “coloureds” – those with mixed ethnic backgrounds – were designated to these race-specific areas. In addition to Langa, which is the city’s oldest township, the group visited Gugulethu, another black African township.

The group began by visiting the Cape Town township of Langa, one of the areas in which black Africans were forced to live during apartheid. Non-white people, including black Africans, Indian South Africans and “coloureds” – those with mixed ethnic backgrounds – were designated to these race-specific areas. In addition to Langa, which is the city’s oldest township, the group visited Gugulethu, another black African township.

“The townships are areas of high poverty, sometimes without electricity or running water,” said Winstead Reichner. “I was very apprehensive about our tour there, because I didn't want to be viewed as someone who was invading someone's home to gawk at how they lived. Once we got there, our local guide made us feel welcome, and made us really approach our time there as a learning experience. He was so enthusiastic about sharing his culture, and it was contagious.”

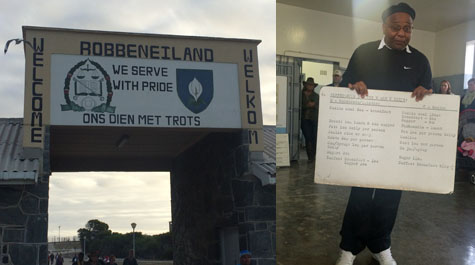

Along with visiting the township, the students continued to learn about the historical context of South African higher education by meeting with people across Cape Town, taking a city tour, and visiting sites including the chambers of parliament; Robben Island, where Nelson Mandela was held for 18 of the 27 total years he was a political prisoner; and city hall, where Mandela gave his first speech just hours after being released from prison in 1990. The tour of Robben Island was given by someone who was a political prisoner himself there.

“To walk through the prison walls with someone leading the tour like that, and to watch him reference experiences as ‘our’ or ‘we,’ that was insightful, for sure,” said Cole.

Similar issues

During the second week in the country, the group visited four universities: University of the Western Cape, a public institution equivalent to what Americans would call a Historically Black College or University (HBCU); the University of Cape Town, a public research university with multiple international partnerships; Cape Peninsula University of Technology, a large, public university that was created about 10 years ago with the merging of two schools; and Stellenbosch University, a predominantly white, public, research university where Afrikaans is the predominant language.

The issue of language is but one of the challenges that the universities are dealing with in a country with 11 official languages, said Cole.

“If you think about giving more people access to education and you think about apartheid, how long it kept people out of education and now you’re making this effort to get more people into colleges and universities, something as simple as what is someone’s mother tongue and what are they most fluent in and what are you teaching in and what language are books produced in – it’s quite complicated,” he said.

Some of the other issues affecting South African higher education right now are similar to those being grappled with by American institutions of higher education, including access and finance – similar, said Cole, and yet different at the same time.

Some of the other issues affecting South African higher education right now are similar to those being grappled with by American institutions of higher education, including access and finance – similar, said Cole, and yet different at the same time.

For instance, public universities in the U.S. are coping with diminished state support by making up the difference with private donors. In South Africa, the public generally does not have the income needed to produce large private donations, said Cole.

Another common source of funding for institutions in both the U.S. and South Africa is graduate-level research. However, South Africa is trying to balance the need for that level of research with the country’s efforts to support undergraduate students, many of whom are the first in their families to attend college following the end of apartheid.

In terms of counseling, the South African universities are again dealing with issues familiar to administrators on American campuses, such as substance abuse and sexually transmitted diseases, but with a special focus on HIV/AIDS. The counseling students on the trip learned a lot by talking with administrators of an HIV/AIDS unit at one university, said Cole, where they heard about education efforts, support for students living with HIV or AIDS and the delicate balancing act of maintaining student privacy while trying to accommodate students’ medical needs.

While administrators in South Africa grapple with such issues, students, too, are playing a large role in shaping higher education in the country, Cole said.

“It’s not like one campus is having a big uprising – this is spread throughout the country where students are really pushing against what are institutional norms and saying, ‘What are we going to do to change this? What are we going to do to be critical of ourselves?’” said Cole. “And that was really energizing for us and refreshing in a way to come back and say, ‘Wow, things can move quicker than they usually do. All leadership doesn’t have to come from top administration – president, provost down – it doesn’t have to.’”

Applying the lessons back home

When Richelle Joe, a May graduate of the counselor education doctoral program, heard that there was a South Africa trip in the works, she immediately wanted to go.

A former history teacher, Joe has long been intrigued by the parallels between apartheid in South Africa and Jim Crow segregation in the United States. And as a counselor educator, she is also interested in dialogues about diversity, race, gender and oppression as they play largely into the development of culturally competent counselors, she said.

“I went to Cape Town curious about how these conversations were taking place in the South African context and how we in the U.S. may grow from an understanding of what is taking place abroad,” Joe said.

“I went to Cape Town curious about how these conversations were taking place in the South African context and how we in the U.S. may grow from an understanding of what is taking place abroad,” Joe said.

Throughout the trip, Joe said she felt embraced by the people of Cape Town, many of whom thought she was South African. She also had the chance to form relationships with colleagues in South Africa with similar interests, creating a foundation for future collaboration. Joe will join the faculty of the University of Central Florida in the fall, where her work will include preparing graduate-level students “to be competent, ethical and culturally sensitive counselors in a diverse society.”

“The trip to South Africa will inform my teaching and supervision and support my efforts to engage students in critical discussions of difficult topics,” Joe said.

It’s a small world

Cole said that offering trips like these to graduate students allows them to see how small the world really is – especially in terms of professional networks.

“In the higher ed program, we’re always talking about international connections and what it means for us moving forward because, with the use of technology now, it’s so easy to be connected to everyone from a professional standpoint,” he said. “But even looking at the student activism and to hear students there say, ‘Wow, I saw the hashtag for Ferguson in the U.S.,’ or what was happening in Baltimore, and I’m just like, ‘Whoa, we are really connected,’ and you miss that experience if you don’t try to get up on those opportunities.”

Although trips like this are priceless in the figurative sense, Cole is very aware that they do have a cost – both in money and time – and that not every student may be able to have such an opportunity. That’s why keeping the conversations going on campus when faculty members and students return from such experiences is so important, Cole said.

“Even more important than being able to go out of the country and physically meet with people is at least being able to get into those conversations happening with people who have gone abroad,” Cole said. “It really is a privilege to go abroad and study like that and engage people – just as much a privilege to be able to come back and share with others what we’ve experienced.”